Want to share this article?

Offshore Platform Decommissioning in the US

Offshore oil and gas wells aren’t endless faucets, meaning the extraction infrastructure at some point will become useless once the well is exhausted.

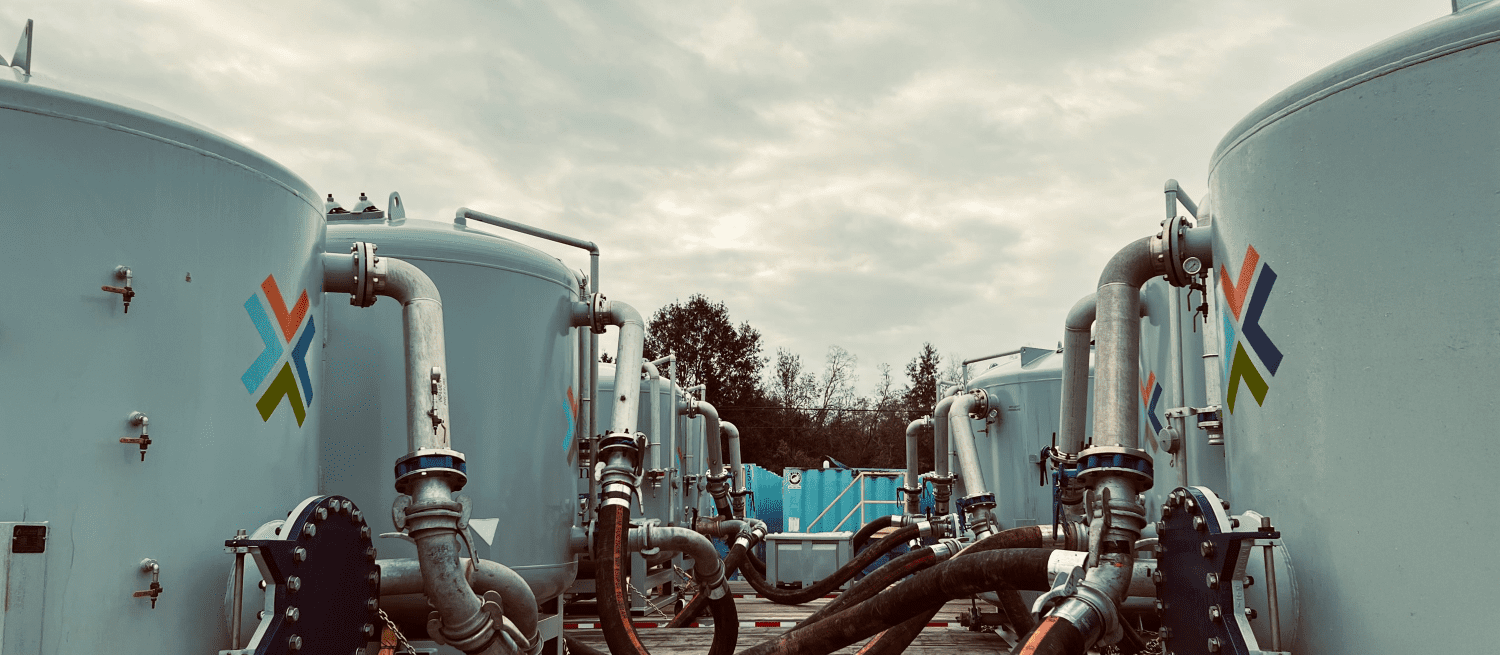

Yet the infrastructure can’t just be allowed to sit unused; over time it begins to become an environmental hazard. As such, these offshore facilities must go through a rigorous process known as decommissioning – the cessation of oil, gas, or Sulphur operations.

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) estimates the offshore energy industry averages 130 offshore platform decommissions per year. In the United States, the decommissioning process is in part regulated by the BSEE and 30 CFR Part 250, which details how wells must be plugged, platforms removed, pipelines shut down, and clearance provided. Additional regulations in September 2010 issued by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement (BOEMRE) have further controlled how long unused wells can remain idle before being declared temporarily or permanently abandoned.

Decommissioning an offshore platform is a multi-phase process that involves reviewing contractual obligations, submitting applications and reports, evaluating environmental impact, removing and disposing of equipment, and ensuring proper site clearance. The process begins well before the reservoir runs dry, often several years in advance (particularly in the Pacific and Alaska regions). Once regulatory paperwork and permitting is in order, the platform infrastructure is reinforced; modules cleaned, separated, and removed; and underwater jackets prepared. Later, the well itself must be plugged or abandonment procedures applied to it to ensure leaking will not occur. Any additional topside structures are removed, while platform components must then be later severed at least 15 feet below the mudline for removal by barge. Any remaining pipelines, cables, and debris must then be cleared to meet clearance requirements.

In special cases in the U.S., an offshore platform doesn’t need to be completely decommissioned; it can instead be partially deconstructed or toppled to create an artificial reef. Eligibility for the National Artificial Reef Plan is largely determined by a collection of other entities, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, the Army Corp of Engineers, and BOEMRE. If found eligible, the operator can then apply to the BSEE to bypass several of the normal decommissioning requirements and convert the rig into an artificial reef, though environmental requirements must still be met.