Want to share this article?

Challenges of Subsea Processing

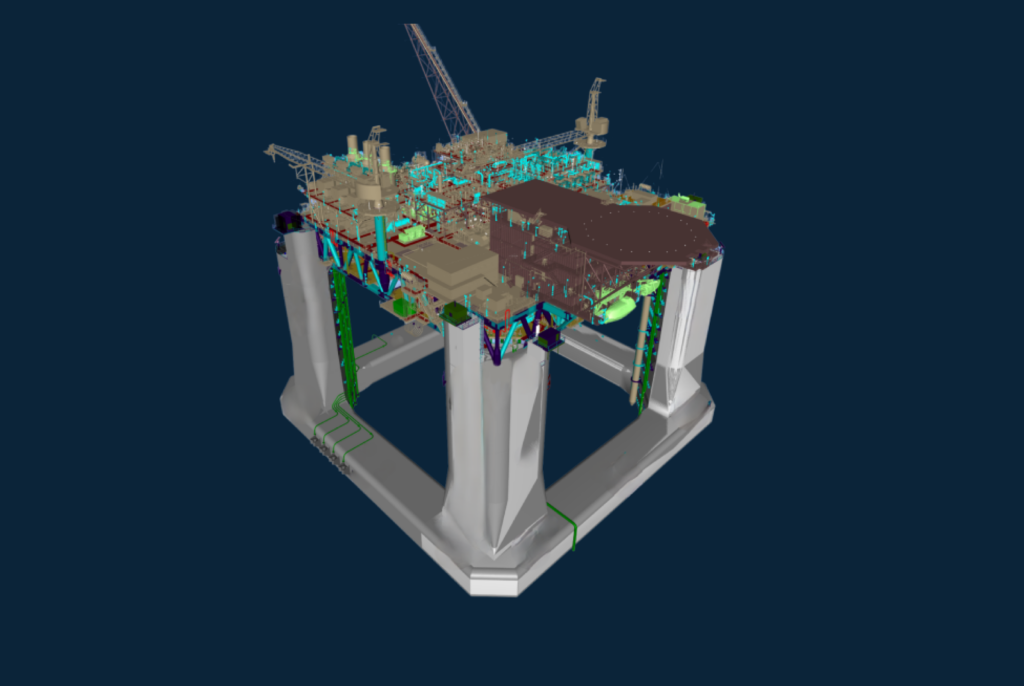

Subsea processing essentially takes the traditional manned topside production platform and places it, unmanned, at the bottom of the sea.

But why do this? According to international certification body DNV GL and oil and gas consultancy Rystad Energy, subsea brownfield updates can boost production on existing fields and greenfield installations can make deepwater fields — previously not thought to be viable — more economically feasible. Major companies such as Petrobas, Shell, Statoil, and Total have largely driven this technology and for good reason: it requires significant capital investment. For example, Total’s subsea Moho Nord project went online in December 2015 and cost nearly $10 billion to implement. But these major companies obviously share a similar view to BMI Research, one that finds sizeable deepwater discoveries with long-term production value able to “counter-balance times of weak commodity prices.”

A significant portion of investment into long-term subsea production platforms is wrapped up in research into new technologies. Any associated components must operate reliably and for several decades at intense pressures and temperatures as low as 4° C. Companies like Siemens push the boundaries of electrical and networking components, developing and testing materials that can withstand the torturous conditions of deep water. “It’s a major challenge to find components that can withstand such extreme conditions, because no manufacturer offers products that are especially designed for such depths,” said Siemens engineer Jan Erik Lystad in a tech review piece for the company in April 2015.

But as these technologies are developed, greater opportunity arrives for those looking to the long term. Subsea boosting, which relies on specially designed subsea pumps to enhance well stream pressures, has matured into one of the most developed deepwater production technologies available today. Subsea separation processes that split out water and other liquids from oil and gas at the seabed aren’t far behind. Other applications such as subsea water injection and subsea compression (for increasing recovery rates at the seabed) are less mature but still being tested. Regardless, companies like Statoil are setting their sights on the ultimate goal of creating a full-scale production facility on the ocean floor by 2020, an aggressive one to be sure. Though Rystad Energy finds “the current downturn in the market might be a bump in the road in terms of realizing the subsea factory,” they and others are still optimistic subsea developments will eventually provide long-term value as long as significant offshore field discoveries continue.